Détournement as a Tool for Reclaiming the Female Image

As part of my campaign Reclaiming the Gaze, I began experimenting with détournement — a method of subverting mass media by reworking existing imagery to challenge its original message. This idea came after a visiting ex-student introduced it to me during a discussion about my project. I’d never heard of it before, but after researching the concept, I realised it was completely aligned with the aims of my work.

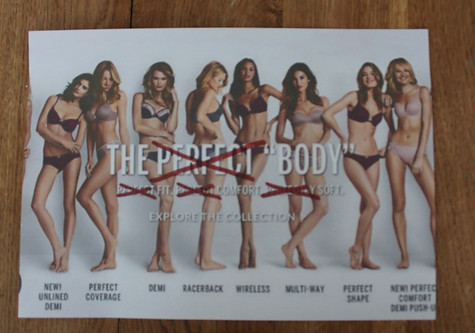

I began collecting and printing out fashion advertisements, model imagery, and promotional materials from fast fashion brands like SHEIN, PrettyLittleThing, and H&M — all of which target young women and heavily push idealised, often unattainable beauty standards. Using pens, markers, and collage techniques, I physically altered these images by drawing over them, adding words, symbols, emojis, and contrasting imagery — deliberately breaking the polished, commercial aesthetic and reclaiming the message.

Reclaiming the Gaze

This hands-on process became a powerful and personal way to critique the harmful narratives these brands put out, particularly around body image, sexuality, and consumer manipulation. Each détourned image serves as an act of protest — turning what was once passive, idealised, and objectifying into something raw, honest, and empowering. It’s about re-authoring what we see and who gets to be seen.

By disrupting the visuals young women are constantly exposed to, my détournement work creates space for reflection and conversation — asking questions like: Why are these bodies celebrated and others erased? Who profits from our insecurities? And what happens when we take back control of the image?

“Love Your Curves” – But Whose Curves?

This détourned image is taken from a well-known Zara campaign that used the slogan “Love your curves” — but featured two extremely slim models. When I first saw this, I found it so jarring and contradictory that I felt I had to respond. By drawing devil horns and adding the phrase “CAN’T WIN” over the image, I wanted to highlight the complete hypocrisy behind the message and how damaging it can be for young women.

For women aged 16–25, who are often navigating issues of self-worth and body image, this type of advertising can be really harmful. When brands like Zara label thin bodies as "curvy," it sends a confusing and unrealistic message about what “curvy” is even meant to look like. It reinforces the idea that even to be curvy, you still have to conform to a certain (thin) ideal — which is completely unrealistic for most women.

“Love Your Curves” – But Whose Curves?

Through détournement, I’m able to visually expose the gaslighting effect of these campaigns — where the fashion industry pretends to be inclusive or body-positive, while still promoting the same narrow standards of beauty. Writing “CAN’T WIN” across the image expresses how women are constantly set up to fail — whatever our body type, it often feels like we’re never enough.

For me, this piece is part of a wider movement within my project — using visual protest to challenge the toxic messaging we’re constantly exposed to. It questions who is allowed to be seen and celebrated in fashion media, and it exposes how damaging false empowerment slogans can be when they mask exclusion and promote insecurity.

Why is detournment important?

This work is really important to my movement because it gives me a direct, visual way to challenge the toxic messages that dominate fashion advertising. By using détournement, I’m able to take back control of these images and flip their meaning — turning them into a critique of the beauty standards and pressures placed on women today. It’s a way for me to call out the industry’s manipulation, especially in how it targets women aged 16–25 with unrealistic ideals and false empowerment slogans.

These edited images reflect how I, and so many other women, have felt when faced with fashion campaigns that claim to be inclusive but actually do the opposite. My movement is about exposing that contradiction and encouraging others to see through it too. It’s also about giving a voice to those who’ve felt excluded, unseen, or “not enough” because of how their bodies are represented — or not represented — in the media.

This process has helped me articulate the frustrations I’ve carried for years around body image, and it’s become a way of reclaiming my own narrative as an artist and woman. These visuals aren’t just protests — they’re part of a bigger statement I’m making through my entire project: that fashion can and should do better.